From Fairclough and Leary, Textiles by William

Morris and Morris & Co. 1861-1940.

I. Morris & Company

During its

eighty-year existence,1 Morris & Company2 made (or

marketed) not only textiles, but stained glass, wallpapers, furniture, tiles

and other pottery and metalwork, as well as linoleum. jewellery and stamped leather. William Morris had so

much ebullience and energy that pattern designing was only one activity among

many. Nevertheless textiles were, with stained glass, the most important part

of Morris & Co.'s business, and were peculiarly Morris's own. though a small minority of fabric patterns were by others.

It is also in his textiles that Morris as a pattern-maker, a design theorist. and an entrepreneur, can best be studied. as these provide striking examples of his susceptibility to

historical influence and of his manufacturing methods.

Morris arrived

at Oxford in 1853 already in love with the Middle Ages. and he was to become a

considerable medieval scholar, whose opinions were sought by the Bodleian

Library and the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum); this scholarship increasingly inspired the structure of his patterns.

It was also his medievalism that led him, in 1856, to become a pupil of the

architect G.

E. Street. in whose office he first met Philip Webb. When

Street moved from Oxford

to London a few months later, Morris shared lodgings at 17 Red Lion Square. Bloomsbury. with Edward

Burne-Jones, his closest Oxford

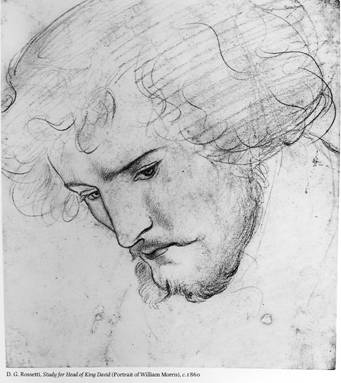

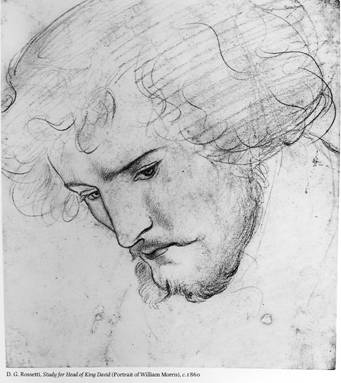

friend. Here they came under the influence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

who persuaded Morris to become a painter. He had

already tried his hand at carving, illuminating and embroidery, and when his

part in Rossetti's scheme for frescoes in the Oxford

Union convinced him that he would never be a great artist. it

was to the decorative arts that he returned.

In 1859 he

married Jane Burden, and with an income of about £900 a year, he was able to

realize his ideal of a

_ perfect artistic house. Although Red House,

which Philip Webb built for them in an orchard at Upton. near Bexley Heath. was not particularly

novel in style. the interior was to be elaborately

furnished as a medieval palace in miniature, with painted decoration and

stained glass designed by Burne-Jones, heavy gothic furniture by Webb, and

embroideries by Morris.

Two older members of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, Rossetti

and Ford Madox Brown. were also involved in

the decoration of Red House. It was apparently Madox

Brown who first suggested. perhaps frivolously. that they should combine to form a decorating business, and

Morris. Superior figures: see References

p. 73.

Marshall,

Faulkner & Co. was set up in April 1861. The partners, Morris, Burne-Jones,

Webb, Rossetti, Madox

Brown, Charles Faulkner (an Oxford

mathematician) and Marshall (a surveyor friend of Madox

Brown) put in a nominal £1 each. The firm was to be a co-operative of artists

producing their own designs for limited hand production. Morris was manager,

and the working capital was a £100 loan from his mother. They survived principally

on commissions from a few sympathetic High Church architects; much of the firm's best stained glass was made in the 1860s,

and this was the most important part of the business. Though exciting, these

years were not quite the revolutionary crusade against the bad design of the

age that Morris's first biographers claimed. Morris and his friends owed much

to the teachings of Ruskin and the example of Pugin,

and one is reminded elf the group of artists associated with Sir Henry Cole's

'Felix Summerly' venture.

At first Morris

continued to live at Upton,

and though it became increasingly important to him, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner

& Co. remained a somewhat amateurish undertaking to which all the partners

contributed. In 1865 this began to change, as Morris could no longer cover the

firm's deficit from his dwindling private income. He reluctantly moved back to London, finding the firm larger premises at 26 Queen Square, where he lived in part of the house, and became

increasingly the dominant partner. The move coincided with the appointment of

Warrington Taylor as business manager; he forced Morris to stop producing work

below cost and to control his erratic output. When Taylor died of consumption in 187°, the Company was

profitable, though several of the original partners had dropped out, leaving

Morris, Burne-Jones and Webb as active members. This period saw a growth in

secular decorating work, which caused a demand for patterned furnishing

textiles, and made it possible to finance new lines. In the early 18 70S Morris

began to design carpets for outside production, made his first design for

printed

cotton, and returned to wallpapers. Meanwhile more

orders for stained glass were coming in, and this increase in business caused a

crisis within the firm, as Morris, for long the major participant, wanted to

reconstruct it under his sole proprietorship. All the partners had a legal

claim on the profits and assets, and three of them, Madox

Brown, Rossetti and Marshall, had to be bought out

after six months of embittered arguments. The firm was then reregistered as

Morris & Co. on 25 March, 1875.

Marshall,

Faulkner & Co. was set up in April 1861. The partners, Morris, Burne-Jones,

Webb, Rossetti, Madox

Brown, Charles Faulkner (an Oxford

mathematician) and Marshall (a surveyor friend of Madox

Brown) put in a nominal £1 each. The firm was to be a co-operative of artists

producing their own designs for limited hand production. Morris was manager,

and the working capital was a £100 loan from his mother. They survived principally

on commissions from a few sympathetic High Church architects; much of the firm's best stained glass was made in the 1860s,

and this was the most important part of the business. Though exciting, these

years were not quite the revolutionary crusade against the bad design of the

age that Morris's first biographers claimed. Morris and his friends owed much

to the teachings of Ruskin and the example of Pugin,

and one is reminded elf the group of artists associated with Sir Henry Cole's

'Felix Summerly' venture.

At first Morris continued to live at Upton, and though it became increasingly important to

him, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. remained a somewhat amateurish undertaking

to which all the partners contributed. In 1865 this began to change, as Morris

could no longer cover the firm's deficit from his dwindling private income. He

reluctantly moved back to London,

finding the firm larger premises at 26 Queen Square, where he lived in part of the house, and became

increasingly the dominant partner. The move coincided with the appointment of

Warrington Taylor as business manager; he forced Morris to stop producing work

below cost and to control his erratic output. When Taylor died of consumption in 187°, the Company was

profitable, though several of the original partners had dropped out, leaving

Morris, Burne-Jones and Webb as active members. This period saw a growth in

secular decorating work, which caused a demand for patterned furnishing

textiles, and made it possible to finance new lines. In the early 1870s Morris

began to design carpets for outside production, made his first design for

printed cotton, and returned to wallpapers. Meanwhile more orders for stained

glass were coming in, and this increase in business caused a crisis within the

firm, as Morris, for long the major participant, wanted to reconstruct it under

his sole proprietorship. All the partners had a legal claim on the profits and

assets, and three of them, Madox Brown, Rossetti and Marshall, had to be bought out after six

months of embittered arguments. The firm was then reregistered as Morris &

Co. on 25 March, 1875.

At first Morris continued to live at Upton, and though it became increasingly important to

him, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. remained a somewhat amateurish undertaking

to which all the partners contributed. In 1865 this began to change, as Morris

could no longer cover the firm's deficit from his dwindling private income. He

reluctantly moved back to London,

finding the firm larger premises at 26 Queen Square, where he lived in part of the house, and became

increasingly the dominant partner. The move coincided with the appointment of

Warrington Taylor as business manager; he forced Morris to stop producing work

below cost and to control his erratic output. When Taylor died of consumption in 187°, the Company was

profitable, though several of the original partners had dropped out, leaving

Morris, Burne-Jones and Webb as active members. This period saw a growth in

secular decorating work, which caused a demand for patterned furnishing

textiles, and made it possible to finance new lines. In the early 1870s Morris

began to design carpets for outside production, made his first design for

printed cotton, and returned to wallpapers. Meanwhile more orders for stained

glass were coming in, and this increase in business caused a crisis within the

firm, as Morris, for long the major participant, wanted to reconstruct it under

his sole proprietorship. All the partners had a legal claim on the profits and

assets, and three of them, Madox Brown, Rossetti and Marshall, had to be bought out after six

months of embittered arguments. The firm was then reregistered as Morris &

Co. on 25 March, 1875.

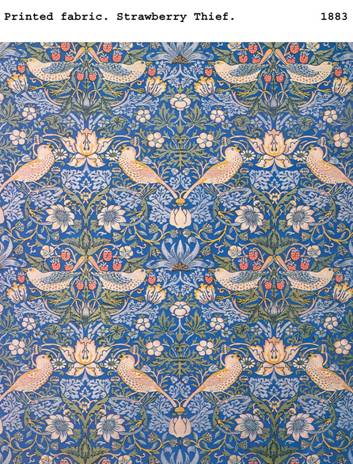

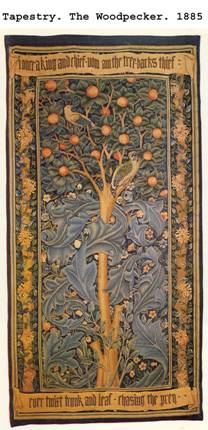

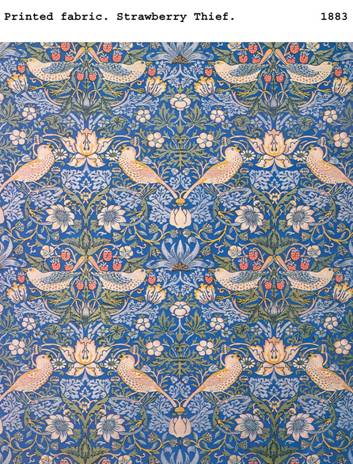

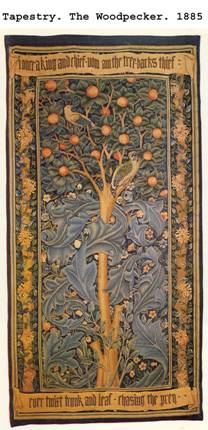

The six years

that followed, 1875 to 1881, were perhaps the most important of Morris &

Co.'s long history. William Morris designed most of his chintzes and machine-made

carpets; he experimented with ancient dyes, and set up his own small dye house;

the firm began weaving his silks and making hand-knotted carpets and

traditional high-warp tapestries. In 1877 the volume of stained-glass work

declined when Morris set up the Society for the Protection of Ancient

Buildings, and declared that he would accept no more commissions for glass in

old churches except under special circumstances. This change in direction was

courageous as the firm had made a loss of £1,023 on printed textiles in

1875-76, but by 1880 Morris's chintzes and woven fabrics were making a handsome

profit, and subsidizing the much more expensive hand-made tapestries and

carpets. The woven textiles were still woven outside on big power-looms. The

chintzes were hand blocked, but, until 1883, by Wardle & Co. and not by

Morris's own employees. Morris hated the ability of the machine to dehumanize labour and to debase design, but had he not been producing

only small quantities of textiles for a limited market, and had he been able to

afford it, he would have bought a power-loom, for, as he said in 1884, the

historic methods of weaving 'are still in use today with no more variation of

method than what comes from the application of machinery. . . . These variations. . . are of little or no importance from the

artistic point of view, and are only used to get more profit out of the

production of the goods; they are incidental changes, and not essential.' 3

Though the

production of embroideries, tapestries and knotted carpets could not be

mechanized (and this gave him much satisfaction), there was a marked

inconsistency between theory and practice, as these textiles were laboriously

made in small quantities for the homes of the very rich by people who were

allowed no real creative freedom to interpret Morris's designs.

The designer's

feeling for materials and for the structure of a pattern has given Morris's

textiles a timeless quality, but they owed their initial commercial success not

only to their inherent charm and to Morris's 'constant artistic supervision',4

but also to the sound business sense with which he negotiated contracts with

suppliers. He was also getting a surprisingly wide use out of his rapidly

growing stock of patterns, using the same design for a woven hanging and a Kidderminster carpet, or for a chintz

and a wallpaper, returning to a small number of themes, and offering patterns

in several colour-combinations or weights.

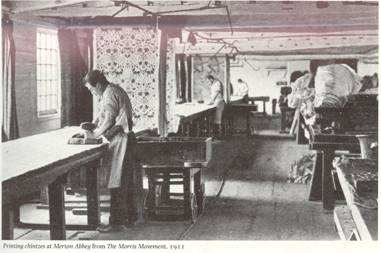

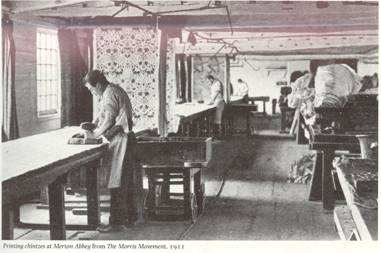

The growing

textile business was more than the Queen Square premises could hold. He toyed with the idea of

moving the firm to Bloxham in the Cotswolds,

before deciding on an 18th-century mill on the river Wandie

at Merton Abbey, near Wimbledon. This group of weather-boarded buildings was

ideal for a firm which consisted of largely self-contained workshops. and the lease was signed in June I881. It took a couple of

years to establish the Merton Abbey works. but from

1883 Morris was printing chintzes there. and had the

space to start making large tapestries and carpets. though

some of the woven textiles continued to be made elsewhere.

The move to Merton inspired in Morris another

burst of pattern designing which lasted until about 1885. but

it also marked the end of his most active participation in the firm. partly because he now had further to travel and partly

because of his growing interest in politics. In 1884 he was instrumental in

founding the Socialist League, and, after its collapse, the independent

Hammersmith Socialist Society in 1890. In 1885 his daughter, May Morris, took

over the embroidery section, and the day-to-day management of the tapestry and

stained-glass workshops fell, increasingly on his assistant, John Henry Dearle (1860-1932). George Wardle, who had been business

manager of the firm since 1870, remained until 1890, drawing about £1,200 a

year to Morris's £1,800 in 1884. He was succeeded by F. and R. Smith, who

became partners in the firm and joint managers. This change coincided with

Morris's establishment of the Kelmscott Press, which

absorbed much of his remaining energy during the early 1890s, at a time when

his health was gradually failing.

The move to Merton inspired in Morris another

burst of pattern designing which lasted until about 1885. but

it also marked the end of his most active participation in the firm. partly because he now had further to travel and partly

because of his growing interest in politics. In 1884 he was instrumental in

founding the Socialist League, and, after its collapse, the independent

Hammersmith Socialist Society in 1890. In 1885 his daughter, May Morris, took

over the embroidery section, and the day-to-day management of the tapestry and

stained-glass workshops fell, increasingly on his assistant, John Henry Dearle (1860-1932). George Wardle, who had been business

manager of the firm since 1870, remained until 1890, drawing about £1,200 a

year to Morris's £1,800 in 1884. He was succeeded by F. and R. Smith, who

became partners in the firm and joint managers. This change coincided with

Morris's establishment of the Kelmscott Press, which

absorbed much of his remaining energy during the early 1890s, at a time when

his health was gradually failing.

Morris died at

Hammersmith on 3 October, 1896, aged sixty-two. For the previous couple of

years, the Merton Abbey works had been largely run by J. H. Dearle,

who had joined the firm as an assistant in the Oxford Street showroom, and had

been an apprentice in the glass painting room, before becoming Morris's first

tapestry weaver; after Morris's death he was appointed partner and art

director. Dearle had been designing for tapestry and

stained glass for several years, and after 1896 he added patterns for damasks,

chintzes, carpets and wallpapers. He remained Morris's disciple for the rest of

his life, but his work was rarely more than a pastiche of his master's. 5

Morris &

Co. changed little between the early 1890S and 1914, and began to live off its

artistic heritage, offering old designs in new colour

schemes, as well as a few new ones very much in Morris's style. The main

innovation during this period was the sale of reproduction 18th-century

furniture, but even this began before Morris's death. Morris & Co. also

began to repair and sell antique tapestries in the 1890s. For some years the

scope of general decorating business had been considerable, ranging from contracting

for building work, widening doorways or stairs, or fitting fireplaces or panelling, to cleaning curtains or re-upholstering

furniture in material supplied by the customer.6 But according to a

contemporary commentator what made Morris & Co. profitable was 'a considerable

and more or less constant demand for certain wallpapers and cretonnes, and

machine-made carpets and other repeat orders where their prices don't differ

much from ordinary commerce'. 7

In 1905 F. and R. Smith retired as managers, though

they became directors of Morris & Company 'Decorators Ltd, registered as a

private company. The managing director was H. C. Marillier,

and the board included, among others, Dearle and W.

A. S. Benson. A number of changes followed. A good deal more reproduction 18thcentury

furniture was made, and the firm also sold direct copies of antique damasks and

conventional floral chintzes.8 The accession of King George V

brought prestigious commissions for thrones for the 191 I coronation and for

the investiture of the Prince of Wales; for these Morris & Co. received a

Royal Warrant as furnishers to the King.

In 1905 F. and R. Smith retired as managers, though

they became directors of Morris & Company 'Decorators Ltd, registered as a

private company. The managing director was H. C. Marillier,

and the board included, among others, Dearle and W.

A. S. Benson. A number of changes followed. A good deal more reproduction 18thcentury

furniture was made, and the firm also sold direct copies of antique damasks and

conventional floral chintzes.8 The accession of King George V

brought prestigious commissions for thrones for the 191 I coronation and for

the investiture of the Prince of Wales; for these Morris & Co. received a

Royal Warrant as furnishers to the King.

The First World

War caused some disruption, though in October 1917 Morris & Co. moved into larger showrooms, until a new building was taken at Chalk

Farm in 1927. The firm changed its name, again, to Morris & Company Art

Workers Ltd in 1925, and its comfortable 'Queen Anne revival' style was still

quite popular, for 'all Morris fabrics, papers, carpets, etc. go well and

harmoniously together and make a perfect scheme of decoration also with old

furniture and antique rugs'. 9 An upholsteress

was to remember that 'the work was extremely high class', and that 'all the

fashionable people', 10 among them George Bernard Shaw and the Duke

of Marlborough, went to the George Street showroom, which now sold antiques and

contemporary studio-pottery in addition to the firm's textiles and furniture.

There were a few new designs for tapestry, and though some of these are not

unattractive, they had absolutely no effect on the gradual decline of the

business, and prove how far the firm had gone down a creative blind alley, By the end of the decade even the printed and woven

furnishing fabrics were becoming increasingly uncompetitive. J. H. Dearie was rigorous in maintaining standards of quality,

but in 1930 he was writing to May Morris, whose participation in the business

had ceased in about 1922, of how he longed for some relief 'from constant

compulsory attendance', and of how 'we find that vegetable dyes are less and

less possible which is of course very regrettable. . . so simple a palette is

about all your father used . . .',11 There was a staff of about

fifteen at Merton Abbey, 'creeping about in the gloom, waiting for instructions

from head office, who were transmitting orders from a dwindling band of clients

as the taste of the time changed' .12 It all reeks of nostalgia and tradition,

and the few art school trained recruits were not encouraged to stay. There was

little new machinery and no new ideas.

J. H. Dearle died in harness in 1932, and was succeeded by his

son Duncan Dearle (1893-1954), but he, according to

one of the weavers, 'was not particularly interested in the work,

and spent more time playing his clarinet'. 13

From 1936 Morris & Co. was faced

with mounting deficit, and on the outbreak of war in 1939 the board, still

headed by H. C. Marillier, decided that the firm

could not continue. It went into voluntary liquidation on 21 May, 1940, having survived virtually all the Arts and

Crafts guilds it had inspired. Within a decade the firm's printed patterns were

being reproduced, and today, though mostly rollerprinted

in modern pigments, they are more widely known than ever.

At first Morris continued to live at

At first Morris continued to live at  The move to Merton inspired in Morris another

burst of pattern designing which lasted until about 1885. but

it also marked the end of his most active participation in the firm. partly because he now had further to travel and partly

because of his growing interest in politics. In 1884 he was instrumental in

founding the Socialist League, and, after its collapse, the independent

Hammersmith Socialist Society in 1890. In 1885 his daughter, May Morris, took

over the embroidery section, and the day-to-day management of the tapestry and

stained-glass workshops fell, increasingly on his assistant, John Henry Dearle (1860-1932). George Wardle, who had been business

manager of the firm since 1870, remained until 1890, drawing about £1,200 a

year to Morris's £1,800 in 1884. He was succeeded by F. and R. Smith, who

became partners in the firm and joint managers. This change coincided with

Morris's establishment of the Kelmscott Press, which

absorbed much of his remaining energy during the early 1890s, at a time when

his health was gradually failing.

The move to Merton inspired in Morris another

burst of pattern designing which lasted until about 1885. but

it also marked the end of his most active participation in the firm. partly because he now had further to travel and partly

because of his growing interest in politics. In 1884 he was instrumental in

founding the Socialist League, and, after its collapse, the independent

Hammersmith Socialist Society in 1890. In 1885 his daughter, May Morris, took

over the embroidery section, and the day-to-day management of the tapestry and

stained-glass workshops fell, increasingly on his assistant, John Henry Dearle (1860-1932). George Wardle, who had been business

manager of the firm since 1870, remained until 1890, drawing about £1,200 a

year to Morris's £1,800 in 1884. He was succeeded by F. and R. Smith, who

became partners in the firm and joint managers. This change coincided with

Morris's establishment of the Kelmscott Press, which

absorbed much of his remaining energy during the early 1890s, at a time when

his health was gradually failing. In 1905 F. and R. Smith retired as managers, though

they became directors of Morris & Company 'Decorators Ltd, registered as a

private company. The managing director was H. C. Marillier,

and the board included, among others, Dearle and W.

A. S. Benson. A number of changes followed. A good deal more reproduction 18thcentury

furniture was made, and the firm also sold direct copies of antique damasks and

conventional floral chintzes.8 The accession of King George V

brought prestigious commissions for thrones for the 191 I coronation and for

the investiture of the Prince of Wales; for these Morris & Co. received a

Royal Warrant as furnishers to the King.

In 1905 F. and R. Smith retired as managers, though

they became directors of Morris & Company 'Decorators Ltd, registered as a

private company. The managing director was H. C. Marillier,

and the board included, among others, Dearle and W.

A. S. Benson. A number of changes followed. A good deal more reproduction 18thcentury

furniture was made, and the firm also sold direct copies of antique damasks and

conventional floral chintzes.8 The accession of King George V

brought prestigious commissions for thrones for the 191 I coronation and for

the investiture of the Prince of Wales; for these Morris & Co. received a

Royal Warrant as furnishers to the King.