Jirousek, Charlotte. Islamic Clothing. In Encyclopedia of Islam. New York: Macmillan Pub. 2004

ISLAMIC CLOTHING

Charlotte Jirousek

Islamic dress has for centuries been used to symbolize purity, mark status or formal roles, distinguish believer from nonbeliever and identify gender. Traditionally Muslims were admonished to dress modestly in garments that do not reveal the body silhouette and extremities. Head coverings were also expected. However, dress forms vary in different periods and regions, as does interpretation of and adherence to Muslim dress codes. The most prominent forms of Near Eastern dress can be classified as Arab or Turkic/Iranian in form, with degrees of blending between the two modes occurring where interaction between these cultures has been greatest.

Arab dress can be seen from northern Syria to North Africa. The basic dress of both men and women is based on the simple tunic, an unfitted garment pulled on over the head, common in the region since Roman times( qamīs or thawb). The earlier form of Arab dress, unseamed wrapped garments (izār and ridā´ ), have survived as the consecrated garments (ihrām) worn by pilgrims to Mecca. The thawb is well suited to desert heat, providing both protection from the sun and ventilation. A wide unfitted mantle (jallāba or abā; hooded burnus) may also be worn. Typical materials are cotton or fine wool, with dense silk embroidery applied to necklines and borders. To this might be added sashes and shawls. Mens head coverings might be a turban, or a simple shawl bound at the forehead, arranged on the head according to status, affiliation, local usage or practical need. Turbans are the most well known of Muslim headgear, however. Hats or caps may also be worn either separately or under turbans. Womens clothing is based on the same basic garment forms but differs in color, embellishment, materials and accessories. In public womens garments would traditionally be hidden by veils that may cover all parts of the body to the ground or only head, shoulders and face.

Turkic dress was widely influential throughout the Islamic world. The Seljuk Turks emerged from Central Asia, establishing dynasties in Iran and Asia Minor by the eleventh century. By the mid-sixteenth century the Ottoman Turkish Empire encompassed most of the lands surrounding the Eastern Mediterranean.

The traditional Turkish ensemble for either men or women consisted of loose fitting trousers (şalvar, don) and a shirt (gömlek), topped by a variety of jackets (cebken), vests (yelek), and long coats (entâri, kaftan, üç etek). The use of coats and trousers derived from their nomadic origins in Central Asia. Trousers protect a riders legs from chafing, and coats or jackets can be more readily donned or doffed than tunics while on horseback, as required in a variable climate. Layering of garments was an important aesthetic element. Garments were arranged to display the patterns and quality of fabrics on all layers and add bulk to the body image. The more formal the occasion or the higher the status of the wearer, the more layers worn, with richer materials further indicating wealth. Colorful sashes that added mass to the body image also served as a repository for weapons and personal articles. Ottoman Turkish headgear typically involved a brimless hat or cap in a variety of sizes and forms indicating official status, gender, and regional identity. Scarves were usually wrapped into a turban over the hat. The form of the turban indicated status, occupation, religious affiliation, and/or regional origin. Womens scarves were wrapped and tied around the head, frequently in layers, with a larger veil worn over all in public.

Specific forms of dress were worn by Ottoman officials throughout the Ottoman Empire. The nearly five hundred year presence of Ottoman rule throughout much of the Arab world led to some blending of garment forms, particularly in northern Arab regions adjacent to Anatolia, and also in urban Arab centers of the Eastern Mediterranean and North Africa. The adoption of buttoned vests or jackets of silk or wool decorated with embroidery, and the loose fitting trousers called şalvar in Turkish or sirwāl in Arabic are evidence of such borrowings in Arab dress. The dress of Muslim sub-Saharan Africa is derived from that of the Arabs who brought Islam there in the eleventh century.

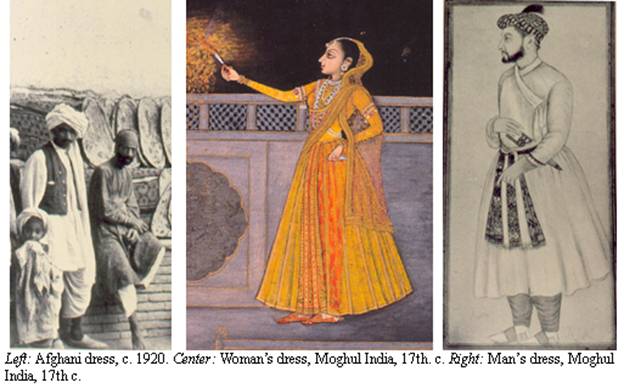

Traditional dress in Iran and Afghanistan share with that of Turkey forms indicative of nomadic origins, with layered coats and şalvar as typical features of dress. These forms were also introduced into Muslim Northern India from Central Asia by the Turkic Gaznevids in the eleventh and twelfth century, and by the Mughuls in the sixteenth century. Such forms are reflected in Mughul court dress, where for men trousers (paijama) were typically combined with front-opening coats or jackets of varying length and cut (angarkha or jama). For women, the characteristic ensemble might include a bodice or tunic ( kurta or choli) and skirt (gaghra), and/or trousers (salwar), as well as a veil. The exquisitely fine and complex silks and cottons of India are a distinctive characteristic of dress from this region.

Modesty in dress was enjoined in Islam for both men and women, although the particulars of pious modesty are not precisely defined in the Quran. The body of Islamic law and scholarship, however, has provided more specific directives that have nonetheless been applied differently in different times and places. Generally some sort of headcovering or veiling (hijab) is mandated for both men and women. In some countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia all women are required to veil, although the forms of veiling vary. In some other societies veils may be a matter of choice.

Throughout the Islamic world, dress has been used to manage distinctions of rank, gender, and religion. Under Ottoman law, for example, dress of the various religious communities within the Empire was regulated, with specific colors and forms of headgear, shoes, and garments defined. Garments, particularly coats, were an important aspect of court ceremonial throughout the Muslim world. The court reception of emissaries, celebration of religious holidays, installation of officials, or honoring of heroes always called for the presentation of ceremonial robes and other textile gifts, with the richness of the fabrics or fur linings a mark of the degree of honor conferred upon the recipient. The wearing of luxurious materials such as silk and gold thread was often restricted, however, although such restrictions were often ignored. The wearing of silk, particularly next to the skin, was widely held to be an impious luxury for good Muslims. A colorful satin cloth which had a cotton weft and silk warp, and therefore a cotton inner surface and a silk outer face, allowed the wearer to conform to this religious admonition while enjoying the luxurious outer appearance of a silk garment. This textile was widely used in the Islamic world, known as kutnu in the Near East, and mashru in Northern India and Pakistan. However, the most pious avoided luxurious materials and colors, and wore clothing of simple wool, cotton, or linen.

Beginning in the nineteenth century, westernization of dress occurred together with modernization of political, military and educational institutions, since initially modernization was officially perceived as consonant with westernization. Also the emergence of a modern textile industry in many regions led to the disappearance of the more costly handmade textiles once used in traditional dress. Since dress had long been closely regulated under Muslim law, departures from traditional dress became highly charged political and social issues. The banning of the turban and the introduction of the fez by the Ottoman Sultan Mahmut II in 1829 (as well as a westernized military uniform) caused great controversy as did similar decrees in Iran in 1873. These reforms were intended to symbolize modernization of military and administrative institutions, yet a century later the fez had become a symbol of Ottoman traditionalism. Following the founding of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk met resistance when he banned the fez in 1925, and even more so when he urged abandonment of the veil for women. Since mandated ideas of proper dress had for centuries been the means of distinguishing Muslim from non-Muslim, these issues continue to have great emotional force throughout the Muslim world. In the 1980s and 1990s dress reemerged as a symbolic flashpoint between religious conservative and secularist elements in Islamic societies.

Bibliography