From Ottoman Costumes: From Textile to Identity. S. Faroqhi and C.

Neumann, ed.

Ottoman Influences in Western Dress

Charlotte Jirousek

Fashion

is a significant area of cultural borrowing that reflects the broader exchanges

of ideas that occurred between the Ottomans and the West. Dress reflected both

personal tastes and cultural values in these societies. A great deal has been

written about the influence of

Western fashion in

The

Fundamental Form of European Dress

In

order to be able to make coherent statements about exchanges of dress ideas

East and West, it is necessary to first define what was characteristic about

the aesthetics of both Turkish and European dress. The essential characteristic

of European clothing was that it revealed more of the contours of the body than

did dress of the East. In the early Medieval period both men’s and

women’s garments were laced to the upper body, and although women’s

gowns were modestly skirted to the ankles, men’s were short enough to

display a well-turned leg, usually encased in closely fitted or laced hose.

Although outer garments such as capes, mantles and hoods were worn for

functional or perhaps for ceremonial purposes, prior to the Crusades trousers

as worn in the East were unknown, as were sleeved, front opening coats. Nor was

the layering of these garments a particularly important aesthetic element in

the early middle ages.

Tailoring-- the use of curved seams and

darts to achieve individual fit-- is a distinctly European invention of the fourteenth century that enhanced the display of the body contours.[1] Men displayed their legs in fitted hose that were separate covers for each leg, suspended from the interior of the upper body garment, also closely fitted. Only much later did men encase their legs in a single bifurcated garment, trousers. For women the legs were enveloped in long skirts, with no bifurcated garment of any kind worn until the mid nineteenth century. The gender division of dress was thus much more pronounced than in Near Eastern dress, with garments of entirely different construction-- hose (later trousers) and skirts each reserved exclusively for one sex.[2] For women, not only was the upper body garment closely fitted, the neck, head and face might be exposed.

Yet within these general aesthetic limitations we see changes so dramatic that an observer from the fifteenth century would be hard put to identify the nationality, or even the rank and occupation of Europeans he might encounter in later periods. Costume historians find it far easier to date European garments that have survived, because fashions changed much more rapidly and dramatically in construction, silhouette and embellishment.

The

fundamental form of Turkish Dress

The Turks trace their origin to the steppes of Eastern Central Asia. There they first appear in history as pastoral nomads, horse riders who followed their herds of sheep and goats. From this lifestyle a form of dress evolved that was adapted to life on the move, and the vagaries of climates that could include extremes of heat and cold. The fundamental garments for both men and women were loose trousers, most suitable for riding, with front opening coats and vests or jackets.[3] The coats, jackets, and vests could be layered over a shirt for warmth. They had the advantage over closed tunics in that they could be removed easily a layer at a time as needed, even when on horseback.[4] Sashes are used to close garments and also serve as receptacles for personal items or weapons. Distinctions of gender or status are indicated by differences in other accessories, such as jewelry and above all, headgear. Prominent and often complex headgear was a particular characteristic of Ottoman dress for both men and women. Details of accessories, textile embellishment, textile choice, and the particular combinations and layering sequence of garments worn further distinguished gender, class, and particular clans or communities .

The

wearing of many layers always had been a characteristic of ceremonial or

festive dress, and was a sign of wealth and status.[5]

The layering of coats is a particular characteristic of Turkish dress, creating

a silhouette that muffled the body form and equated luxurious dress with

modesty and bulk. The layers were not merely worn one on top of the other, they

were designed and arranged so as to reveal the materials of all the layers, to

sumptuous effect. The significance of layering as a broader aesthetic and spiritual concept is

deeply embedded in the culture. There is an array of special textiles, often

elaborately embellished, used as covers or wrappers for gifts, or storage of

especially valued items which may themselves be articles of dress or textiles.[6]

Here again formality is associated with layers. In Islamic decorative arts, the

layering of intricate patterns one on top of the other is seen as a spiritual

metaphor for the nature of the divine order, seemingly incomprehensible, but in

fact planned and meaningful.[7]

The significance of layering as a broader aesthetic and spiritual concept is

deeply embedded in the culture. There is an array of special textiles, often

elaborately embellished, used as covers or wrappers for gifts, or storage of

especially valued items which may themselves be articles of dress or textiles.[6]

Here again formality is associated with layers. In Islamic decorative arts, the

layering of intricate patterns one on top of the other is seen as a spiritual

metaphor for the nature of the divine order, seemingly incomprehensible, but in

fact planned and meaningful.[7]

Once Islam was adopted, Turks also adopted the tradition, based in the teachings of the Prophet, that Muslims must be distinguished by their dress from non-Muslims.[8] Turbans for men, veiling for women and the wearing of certain colors and fabrics became markers of the Muslim. In Ottoman society, which included many ethnic and religious groups, dress became a particular marker of any religious affiliation, established by law.[9]

These forms remained essentially unchanged over centuries, particularly for men, except for dynastic changes in headgear. For women, the essential forms also remained the same although there were some gradual changes in silhouette, materials and accessories. The fact that many items in the royal wardrobes preserved in Topkapı cannot be dated to a specific reign, and perhaps not even to a specific century confirms the stability of Ottoman dress forms, especially in earlier periods. This slow rate of change had begun to accelerate in the eighteenth century, however, as a wider range of consumer goods became available and exposure to new tastes and fashion ideas proliferated.[10]

Sources

of fashion ideas

The

contacts between Ottomans and Europeans were far more extensive than is often

suggested. It is easier to document the presence of Europeans-- merchants,

diplomats, and tourists in Ottoman lands than the other way around because so

many have left us memoirs of their experiences, starting with Breydenbach in 1481,

and including such famous travel writers as de Nicolay, de Busbecq and many

others.[11]

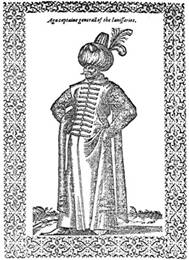

The travel accounts were widely published. Many offered both descriptions and

illustrations of Ottoman dress to a select but influential audience. These

accounts and their illustrations were republished, quoted, and copied by

others. Costume books became a popular commodity beginning in the sixteenth

century.[12]

Artists such as Giovanni Bellini and Melchior Lorck were early travelers to the

Ottoman court. Their works provided source material for many other painters and

printmakers who sought to include the Turk in their representations of the

world. Even in the early medieval period features of Muslim dress had been used

in portrayals of Near Eastern figures incorporated into Biblical scenes.  By

the late fifteenth century Ottoman costume was meticulously and often quite

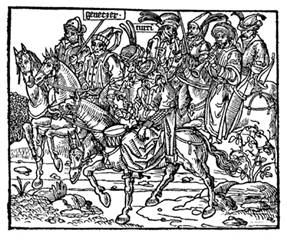

accurately depicted. (Left; 1481 image of Turks, Breydenbach) Paintings

recording panoramas of great battles against the Turk, diplomatic receptions,

and historic events that involved Middle Eastern figures were displayed in

palaces, churches and council chambers in every part of

By

the late fifteenth century Ottoman costume was meticulously and often quite

accurately depicted. (Left; 1481 image of Turks, Breydenbach) Paintings

recording panoramas of great battles against the Turk, diplomatic receptions,

and historic events that involved Middle Eastern figures were displayed in

palaces, churches and council chambers in every part of

Actual

Ottoman clothing returned to

“When

you go from

Clothing

was also important as a ceremonial gift in the

On

the other hand, Ottoman visitors to

Trade

was itself an extremely important source of cultural and fashion exchange. The

history of the textile trade between

Of course, textiles and dress were far from being the only cultural borrowings that occurred. Music, decorative design in architecture and furnishings; philosophical, literary and artistic ideas; even foods, as well as technologies and military ideas also traveled between both worlds. Theater and Opera both became venues for the presentation of Ottoman dress, costume for the many productions with Turkish themes or characters that can be documented from the sixteenth century onward.[21] Although theatrical productions often distorted Ottoman dress to suit local notions of beauty and fashion, images of such theatrical “Turkish” costume tells us just what features of Ottoman dress Europeans considered both attractive and distinctively “Eastern”. Fanciful representation of Turkish costume frequently involved layered or asymmetrically draped or loose garments for both men and women, turbans and enormous plumes for men, or elaborate headdresses with plumes and trailing veils for women. However, these features were embellishments applied to the typical tailored garment forms, with doublet and hose or corset and skirts. However, by the eighteenth century we see images of famous actors and actresses in Turkish dress that appear to be somewhat more accurate; indeed, at least one actress, Madame de Favart, had her costume sent from Constantinople.[22] By this date, the stylistic distance between Eastern and Western dress was not so vast, and so accuracy became more appealing and acceptable.

Historically, there has been a tendency for fashion to be borrowed from centers of perceived power, even when the source is an adversary. This tendency can be readily seen in the twentieth century, where American fashions have permeated virtually every corner of the world; witness the television images of Anti-American protestors in China following the bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Kosovo, in which mobs are united not only in their disapproval of U.S. actions but also in their uniform of levis, T-shirts, running shoes and baseball caps. Similarly the dress of the seemingly invincible Turk made a great impression on those who faced them in the marketplace and on the battlefield, particularly from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries, although that fascination has never completely gone away. Since fashion systems depend upon planned obsolescence to engender profits, there is a continual need to make fashion “new”. The exotic has long been a source of novelty for fashion leaders seeking fresh ways to enrapture their audience. However, the fashionable have never been scholars of dress, and so are casual in their blending of ideas and in their attribution of sources. Only by comparing the actual garments can one see the likely origins of fashion innovations.

Ottoman

influences in Western dress: Coats and trousers

Coats

and trousers were the essential garments of Turkish men and women. By the

twelfth century front opening coats begin to appear as outer garments worn

initially by scholars and clerics (Left; 14th

century monk). However, trousers, which were a great departure from European clothing

construction, would not be adopted so quickly. The advantages of coats,

however, were more apparent. Coats and jackets or vests, unlike mantles or

cloaks, stayed in place on the body and did not encumber free movement of the

arms. They can also be readily donned or doffed as circumstances require, and

need not be pulled over the head as did the sleeved tunics common to previous

European experience.

However, trousers, which were a great departure from European clothing

construction, would not be adopted so quickly. The advantages of coats,

however, were more apparent. Coats and jackets or vests, unlike mantles or

cloaks, stayed in place on the body and did not encumber free movement of the

arms. They can also be readily donned or doffed as circumstances require, and

need not be pulled over the head as did the sleeved tunics common to previous

European experience.

In religious and scholarly dress, during the First Crusade coats begin to appear that had either no sleeve, like the Arab ~b~ or the short sleeve of Turkish-style outer kaftans designed to show the sleeve of the coat(s) underneath. The adoption of such garments by European clerics coincided with the emergence of scholarly interest in Islamic texts as a source of knowledge on medicine, mathematics, and other subjects. Also we see the appearance in Western dress of the very distinctive Turkic feature of the hanging sleeveB another means by which the Turkish wearer could display the rich fabric of an under coat, through the opening of the partially detached sleeve of an outer coat. The drawings of such coats in European contexts show a different construction than the Turkish examples, but the concept is strikingly similar, and quite new to European fashion.

The

earliest form of this feature are the long extensions of sleeves called

tippets, Both are reminiscent of the Turkish hanging sleeves . The tippet

resembles the effect seen in a quilted silk jacket with chain mail lining,

dated to the fourteenth century, seen in the  Hanging

sleeve effects become increasingly striking in the fourteenth and fifteenth

centuries. Fuller long sleeves

beginning in the late thirteenth century may have a long slit through which the

arm can be inserted. This idea continues to be used in sixteenth century coats.

Hanging

sleeve effects become increasingly striking in the fourteenth and fifteenth

centuries. Fuller long sleeves

beginning in the late thirteenth century may have a long slit through which the

arm can be inserted. This idea continues to be used in sixteenth century coats.

Treatments are extremely varied. as

longer gowns come into vogue, particularly for older men, we see various

arrangements of layered sleeves that permit a closely fitted under-sleeve,

often long and wrinkled and pushed up, and/or with a funnel-shaped cuff turned

back to show a contrasting lining. Both features were common to Turkish,

Persian, and Central Asian coat sleeves even before the Muslim period. The

over-sleeves may be also wide, and either long or short, but designed to reveal the

snugly fitted under-sleeve of the cote or pourpoint.

Treatments are extremely varied. as

longer gowns come into vogue, particularly for older men, we see various

arrangements of layered sleeves that permit a closely fitted under-sleeve,

often long and wrinkled and pushed up, and/or with a funnel-shaped cuff turned

back to show a contrasting lining. Both features were common to Turkish,

Persian, and Central Asian coat sleeves even before the Muslim period. The

over-sleeves may be also wide, and either long or short, but designed to reveal the

snugly fitted under-sleeve of the cote or pourpoint.

Also

by the end of the twelfth century we see the appearance of pelissons, which

are fur-lined outer garments, worn by both men and women.[23]

By the fourteenth and fifteenth century we see fur-lined coats that bear a

striking resemblance to the Ottoman style. From this time on coats, short and

long, become part of the repertoire of fashion.

The

visual effect of layering inevitable with coats is particularly interesting.

Coats are a very important feature of male dress in the first half of the

sixteenth century. A short wide coat is worn that creates an impressive upper

body silhouette without obscuring the essential European feature beautifully

hosed and decorated legs, the fitted doublet, and the ostentatiously displayed

codpiece. The sleeve of the coat is short, permitting display of an elaborately

decorated under-sleeve in the Turkish manner. Loose short coats of this type

first appeared in the 1490s in

The

sixteenth century was a period in which in both war and commerce the Ottomans

were a crucial issue for the European powers. Henry VIII is known to have been

taken with Turkish dress. His chronicler Edward Hall described a fete at the

English court at which Henry

appeared with his retinue dressed as a Turkish Sultan as part of a masquerade.[24]

Toward the end of his reign in 1542, Henry VIII posed for a portrait that is a

striking comparison (apart from headgear) to that of his contemporary,

Süleyman the Magnificent, but because of the pose even more dramatically

resembles that of a later sixteenth-century sultan, Mehmed III .

Another

item of dress inevitably associated with coats is the button. In the early

Medieval period European clothing was normally secured with brooches, pins, or

laces (also known as points). It is part of the Middle Eastern and Central

Asian tradition of coats from an early date. In the Book of Chess of

Alfonso the Wise of Castile a Moor is shown wearing a long gown with buttons,

but buttons were not worn by the Spaniards in the illustrations. Buttons can

also be seen in a Moorish ceiling painting in the  When

trade negotiations were concluded in 1581 between the

When

trade negotiations were concluded in 1581 between the

The

wearing of loose dressing gowns at home, sometimes referred to as banyans

became a fashion in the 1670s. There was a particular fashion for banyans

made of painted Indian cottons[26]

Diarist Samuel Pepys bought Indian gowns, and posed for a portrait in one.

Although initially these gowns were imported from

By

the last quarter of the seventeenth century

The bifurcated trousers or pantaloons long worn in the East begin to appear as sailor’s garments in the late sixteenth century. The garment often referred to as “melon hose”, worn by fashionable men during the later sixteenth century are constructed in the same manner as one type of Turkish şalvar; that is, with draw string waistband and drawstring gathering at each leg-- only shorter, in keeping with the European male penchant for displaying the leg. By the early seventeenth century melon hose had elongated into full breeches, gathered just below the knee and at the waist.

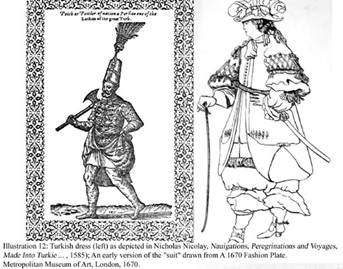

Probably the most notorious example of orientalist influence in western dress is the emergence of the modern men’s suit. The suit would replace the doublet and hose long worn by European men with layered coats and trousers. The appearance of this style is documented in the diaries of Pepys and Evelyn as a new introduction in October, 1666. The essential components of what we know as the suit were trousers or breeches; a single bifurcated lower body garment; the shirt, which had now been exposed as a garment of fashion and not merely underwear; the vest or waistcoat; the outer coat; and the cravat. By the 1660s all of these components had come into use.

The

outer coat appears as a fur-lined hunting coat in the 1620s. It began to be

worn indoors thereafter. Some men took to wearing it without the doublet, and

with the personal linen, the shirt, visible. This style may have originated

with the soldiers habit of wearing their long outer coat without the doublet in

summer.[29]

The corners of the coat were often turned up over the full petticoat breeches

Worn in this way, the resemblance to the Janissary coat is striking. John

Evelyn reports that he reminded King Charles II of a treatise he had written

which argued for dress reform, suggesting a “Persian vest” as a

modest alternative;[30]

after the plague and fire of

The

outer coat appears as a fur-lined hunting coat in the 1620s. It began to be

worn indoors thereafter. Some men took to wearing it without the doublet, and

with the personal linen, the shirt, visible. This style may have originated

with the soldiers habit of wearing their long outer coat without the doublet in

summer.[29]

The corners of the coat were often turned up over the full petticoat breeches

Worn in this way, the resemblance to the Janissary coat is striking. John

Evelyn reports that he reminded King Charles II of a treatise he had written

which argued for dress reform, suggesting a “Persian vest” as a

modest alternative;[30]

after the plague and fire of

Evelyn

reported the interesting coincidence that this ensemble was first seen in

public worn by the King to a performance of a play entitled Mustapha on

October 18 , 1666 in London, a play with a Turkish theme; however, he describes

the new garment as a “Persian” vest, although even the editor of

his diary notes that there are no grounds for the Persian provenance.[31]

Both Evelyn and Pepys had admired Persian dress. Evelyn had seen Persians in

Thus a major paradigm shift in European men’s dress occurs, in which the hose and doublet or tunic that had been the core of European men’s fashion was replaced by the prototypes for trousers, waistcoat, coat, shirt and tie. Another century would be needed to bring the new ensemble to a form fully recognizable as the classic business suit, uniform of the industrial era, but the elements were in place. By the nineteenth century this Near Eastern contribution to Western dress would, in its evolved form, return to its land of origin and begin to transform dress in the East, accompanying the wider reforms that would begin to occur.

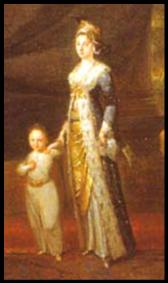

Meanwhile

in  Of

particular interest is the role played by Ottoman women’s dress in the

emerging suffrage movement. In the eighteenth century Lady Mary Wortley

Montagu’s Embassy Letters had painted a sympathetic picture of

Ottoman women that differed markedly from that previously provided by

condescending or fantasy-inspired male writers. She noted in particular that

they possessed legal property rights and

protections that far surpassed the rights of Western women.[32]

She took the comfortable and modest dress of Ottoman women as a symbol of this

admiration, and wore it on her return to

Of

particular interest is the role played by Ottoman women’s dress in the

emerging suffrage movement. In the eighteenth century Lady Mary Wortley

Montagu’s Embassy Letters had painted a sympathetic picture of

Ottoman women that differed markedly from that previously provided by

condescending or fantasy-inspired male writers. She noted in particular that

they possessed legal property rights and

protections that far surpassed the rights of Western women.[32]

She took the comfortable and modest dress of Ottoman women as a symbol of this

admiration, and wore it on her return to  Thus

when Amelia Jenks Bloomer adopted and promoted her “Turkish

trousers”, she was neither the first to do so, nor was her choice of

costume without deeper meaning than mere physical emancipation from corseting

and crinolines.[35]

Thus

when Amelia Jenks Bloomer adopted and promoted her “Turkish

trousers”, she was neither the first to do so, nor was her choice of

costume without deeper meaning than mere physical emancipation from corseting

and crinolines.[35]

The

intense reaction against this sign of women’s emancipation was not

simply a reaction to a garment; the symbolism of Turkish trousers was not

unknown to those engaged in the debate over women’s rights. Although

“Bloomers” did not immediately take hold, and were gradually

abandoned by many feminists, they eventually entered the mainstream of dress;

first as exercise wear for girls, and by the 1890s as cycling wear and beach

wear for women. However, at the same time, nonconformists of rank such as Lady

Archibald Campbell sought to expand the meaning of womanhood in part through

her dress, on one occasion shocking her hostess by appearing at a ball at

Marlborough House dressed in a costume that featured very full trousers, and

eliciting comment on the “Arabian Nights Dress” she wore in the

streets of London. The Crimean War (1853-56) And the Russo-Turkish war (1877)

served to maintain European attention on the

Male dress, which was almost as restrictive as women’s in this period, was also challenged by nonconformists who sought a degree of comfort and escape from the rigidities of public life. In some instances these variations in dress challenged established notions of male gender identity through the adoption of exotic forms of coats and trousers. The adoption of loose knee length trousers, colorful smoking jackets or dressing gown and fezzes for at-home wear were among examples often associated with “aesthetic dress”. Aesthetic style embraced Islamic sources in architecture and interior design as well as fashion, and also was associated with social reform issues of the day.

Headgear

Headgear was one of the most dramatic areas of borrowing from East to West. It is possibly the most prominent and distinctive of Ottoman dress features. Prior to the Crusades, however, headgear was not a particularly important feature of Western dress. Europeans wore hoods or hats to keep off sun and rain, or helmets for protection in warfare, but apart from royal crowns (themselves a borrowing from Byzantine practice) headgear was essentially functional. In contrast, the earliest ancestors of the Turks wore prominent headgear to mark status and affiliation.[36] As Muslims this tradition was augmented by the adoption of the turban, and also of more strict veiling for women. Turkish women had not previously veiled their faces, and even in the Muslim era most were less strictly veiled than were their Arab counterparts.

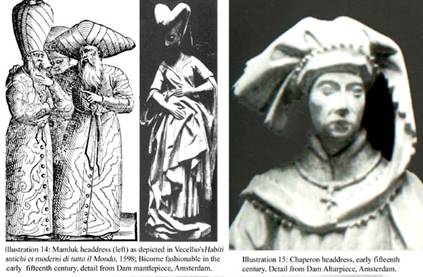

The influence of Ottoman headgear on European fashion particularly between 1380 and 1580, was the subject of an earlier paper.[37] This discussion will summarize that study.

By

the eleventh century the turban, that quintessential mark of the Muslim, had

already spread to

In

the latter half of the fifteenth century

following the conquest of  Both

types were typical of Turkish headgear.

Both

types were typical of Turkish headgear.

Between

1380 and 1450 Turbans were an obviously oriental feature of European dress that

would also reappear at intervals into the twentieth century. Although turbans

had long been known in

During

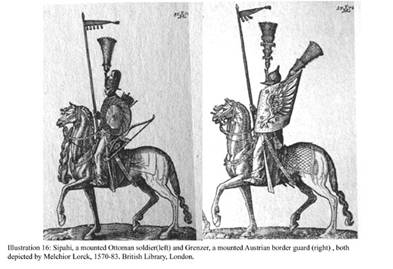

the 1530's Archduke Ferdinand of Austria attempted to fortify the border

country of Slavonia and Croatia by subsidizing a military class known as the

‘Grenzer’ or ‘Uskok’ which paralleled the Ottoman sipahis

(cavalrymen), and resembled them very much in dress. [46].

Among the features of dress shared in common was the use of very tall, and

often very prolific, plumes and crests. From the beginning of the century

elaborate displays of plumes became a prominent feature of German and Swiss

mercenary knights or Landesknecht. It should be kept in mind that since

ostrich plumes and other exotic feathers were generally a commodity to be

obtained only from south of the

During

the 1530's Archduke Ferdinand of Austria attempted to fortify the border

country of Slavonia and Croatia by subsidizing a military class known as the

‘Grenzer’ or ‘Uskok’ which paralleled the Ottoman sipahis

(cavalrymen), and resembled them very much in dress. [46].

Among the features of dress shared in common was the use of very tall, and

often very prolific, plumes and crests. From the beginning of the century

elaborate displays of plumes became a prominent feature of German and Swiss

mercenary knights or Landesknecht. It should be kept in mind that since

ostrich plumes and other exotic feathers were generally a commodity to be

obtained only from south of the

While

by the mid sixteenth century for

the most part women’s headcoverings had ceased to be so prominent, there

is one interesting form that appears in southern

Turbans,

of course reappeared in fashion at intervals for both men and women. In the

eighteenth century men adopted turbans or caps to cover their shaved heads when

they removed their wigs at home. Turbans were adopted by women again in the

early nineteenth century, following the French revolution and during the

Napoleonic wars. Napoleon’s adventures in

Layering

A very distinctive feature of Ottoman dress is the idea of layering. Garments are constructed so as to reveal at neckline and sleeve the varied materials of under layers of garments. Sleeves are partially detached to display under-sleeves. Wide sleeves with trailing ends permit a glimpse of inner sleeve ends. The ends of coats are tucked up into the sash to display both linings and the garments worn beneath. These ideas were not part of the European aesthetic until the twelfth century, when religious and scholarly dress began to include coats that had the short or hanging sleeves of Turkish-style outer kaftans that permitted a glimpse of the sleeve of the coat(s) underneath. The drawings of such robes in European contexts show a different construction than the Turkish examples, but the form is strikingly similar, and quite new to European fashion.

Although many early gowns did not open down the front, images frequently show slits center front (or sometimes at the sides), that as seen in drawings certainly suggest the openings of coats, even if on closer inspection it usually turns out that the opening does not seem to continue up the front. This can be observed both in the skirts of the women’s fitted gown from the mid-fourteenth century, and also the loose long gowns worn by men. However, these slits would serve to reveal the fabric of the garment beneath, and do not seem to have any other function.

During the High Renaissance (1490-1510) the shirt, formerly considered a hidden undergarment, became a layer visible through the gaps between lacing of the sleeve at shoulder, elbow, and through slits along the length of the snug sleeve of the doublet. Women’s dress was similarly treated, with the chemise visible at neckline and through the gaps in the lacing of the sleeve. Over these a loose gown or coat could be worn that revealed all of these layers. The idea of slashing is also added to the vocabulary of dress at the end of the fifteenth century, opening up the garment surface to expose more of the fabrics beneath. Initially slashing simply revealed the garments worn beneath, but by the 1520s slashing evolves into a very contrived and elaborate form of surface ornamentation in which not undergarments but rich linings of contrasting fabric are exposed through the slits. While slashing per se is a peculiarly European aesthetic that seems a predictable result of European taste for constructed, controlled clothing, it also could be argued that the layered illusion achieved might ultimately derive from the Eastern aesthetic concept of layering.

For women, the skirt, previously a solid extension of the upper body garment, also developed a layered appearance beginning in the sixteenth century. The slits observed at the bottom of skirts and gowns a century before now bisect the front of the skirt, revealing a panel of contrasting fabric, frequently a fabric that coordinates with a cuffed under-sleeve emerging from the fuller outer sleeve of the bodice. The form of the garment is stiffly constructed, but layering is clearly intended.

In

the first half of the seventeenth century women’s skirts were full, soft,

and highwaisted. The skirt may still be split down the front, and the overskirt

might be lifted up to further show the underskirt, not unlike the tucked-up ends

of kaftans depicted in images of Turkish figures, male or female. In the latter

part of the century, during the majority of Louis XIV, dress would again become

more stiffly structured and elaborately embellished.. A narrower funnel-shaped

skirt replaces the fuller skirt of the early Baroque, but the style also

featured an overskirt attached to the fitted bodice and gathered up and to the

rear in a form that would come to be called a bustle. Reference is made to a mode a la

Turque that appears following the visit of an Ottoman envoy,

Müteferrika Süleyman Ağa, to the Court of Louis XIV.[52]

The new arrangement of the overskirt that appears by the 1670s corresponds to

the way in which both Ottoman men and women lifted and tucked up the hem of the

outer kaftan revealing the rich fabrics of underlayers.[53]

Turkish contacts with

In

the first half of the seventeenth century women’s skirts were full, soft,

and highwaisted. The skirt may still be split down the front, and the overskirt

might be lifted up to further show the underskirt, not unlike the tucked-up ends

of kaftans depicted in images of Turkish figures, male or female. In the latter

part of the century, during the majority of Louis XIV, dress would again become

more stiffly structured and elaborately embellished.. A narrower funnel-shaped

skirt replaces the fuller skirt of the early Baroque, but the style also

featured an overskirt attached to the fitted bodice and gathered up and to the

rear in a form that would come to be called a bustle. Reference is made to a mode a la

Turque that appears following the visit of an Ottoman envoy,

Müteferrika Süleyman Ağa, to the Court of Louis XIV.[52]

The new arrangement of the overskirt that appears by the 1670s corresponds to

the way in which both Ottoman men and women lifted and tucked up the hem of the

outer kaftan revealing the rich fabrics of underlayers.[53]

Turkish contacts with

The lifted and draped overskirt appears throughout the century, notably appearing in the 1780s as Robe à la Circassiene and Robe à la Turque.[55] Coincidentally, in this period there is a fashion for striped silks reminiscent of the striped patterns commonly used in traditional Ottoman dress.

In

the nineteenth century there are revivals of the lifted, layered look of

bustles, echoing the styles of the eighteenth century. By this time the style

is integrated into the European vocabulary of dress. However, this style does

reappear during the 1820s when European attention turns to the Greek war of independence;

and in the 1870s, when Arts and Crafts style popularized Islamic motifs in art

and design, following the Crimean War and during the Russo-Turkish war. A short

jacket came into style along with the bustle, cut to accommodate the prominent

rear drapery of the skirt, and called a dolman. This term was borrowed from the

Turkish dolaman or dolman, a term for an outer coat. However,

by this period other regions were beginning to contribute exotica to western

fashion, although for the most part this took the form of surface embellishment

rather than alterations in silhouette.

In

the nineteenth century there are revivals of the lifted, layered look of

bustles, echoing the styles of the eighteenth century. By this time the style

is integrated into the European vocabulary of dress. However, this style does

reappear during the 1820s when European attention turns to the Greek war of independence;

and in the 1870s, when Arts and Crafts style popularized Islamic motifs in art

and design, following the Crimean War and during the Russo-Turkish war. A short

jacket came into style along with the bustle, cut to accommodate the prominent

rear drapery of the skirt, and called a dolman. This term was borrowed from the

Turkish dolaman or dolman, a term for an outer coat. However,

by this period other regions were beginning to contribute exotica to western

fashion, although for the most part this took the form of surface embellishment

rather than alterations in silhouette.

Twentieth Century: Globalization of Fashion

The

twentieth century brought a new era in western dress that reflected the

revolutions that were occurring in social, political and economic terms. The

disappearance of the corset as an essential element in women’s dress just

as women obtained the vote is not a coincidence. For fashion designers,

however, the new relaxed silhouette presented a challenge; an entirely new

vocabulary of garment forms was called for. Ideas were taken, as always, from

exotic sources, but in this new age a broader range of options came into play.[56]

Japonisme and Chinoiserie dominated fashion and design during the

first quarter of the century. However, Islamic ideas also continued to be

important. The Bolshevik Revolution caused the renowned Ballet Russe to flee to

The

twentieth century brought a new era in western dress that reflected the

revolutions that were occurring in social, political and economic terms. The

disappearance of the corset as an essential element in women’s dress just

as women obtained the vote is not a coincidence. For fashion designers,

however, the new relaxed silhouette presented a challenge; an entirely new

vocabulary of garment forms was called for. Ideas were taken, as always, from

exotic sources, but in this new age a broader range of options came into play.[56]

Japonisme and Chinoiserie dominated fashion and design during the

first quarter of the century. However, Islamic ideas also continued to be

important. The Bolshevik Revolution caused the renowned Ballet Russe to flee to

Following

the establishment of the Turkish republic, Turquerie became less

prominent in fashion and design, although it has never really disappeared. As

Following

the establishment of the Turkish republic, Turquerie became less

prominent in fashion and design, although it has never really disappeared. As  A

few expatriate Turkish designers have joined the ranks of international couturiers, notably Ozbek

and Caglayan . They have contributed subtle and thoughtful aesthetic ideas that

are clearly drawn from their Turkish roots.

A

few expatriate Turkish designers have joined the ranks of international couturiers, notably Ozbek

and Caglayan . They have contributed subtle and thoughtful aesthetic ideas that

are clearly drawn from their Turkish roots.

The visual language of dress has become a world language, in which increasingly a common vocabulary is shared, although still with numerous local dialects. If fashion is a reflection of its times, then fashion is telling us that culture is increasingly a shared construction in which an increasing proportion of its elements are active collaborators in its creation, not simply raw materials to be used or ignored by a select few. The question is whether this is taking us into a homogenous future in which the rich variation of these elements will be dissolved , or one in which diversity will be valued.

Bibliography

Ardalan, N., & Bakhtiar, L., The Sense of Unity: The Sufi tradition in Persian architecture, Publications of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Vol 9 (Chicago and London, 1973).

Arnold,

Janet, Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlocked (

Baines,

Barbara, Fashion Revivals from the Elizabethan age to the Present Day (

Baker,

Patricia, “The

Batterberry, Michael and Ariane Batterberry, Fashion: The Mirror of History (New York, 1977).

Berker,

Nurhayat, Türk İşlemeleri, Yapı Kredi Koleksiyonları

(

Boucher, Francois, 20,000 Years of Fashion (New York, 1987).

Braudel, Fernand, The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism in the 15th-18th Century, Vol 2 (New York, 1979).

Çağman, Filiz, “Women's

Clothing” in Woman in

Contini, Mila, Fashion

from Ancient

Davis,

Fred, Fashion as Cycle, Fashion as Process (

de

Busbecq, Ogier Ghiselin, The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq,

Imperial Ambassador at

De

Marly, Diana, Fashion for Men: An Illustrated History (

Evelyn,

John, Diary, edited by E. S. Beer, Vol 3 (

Gervers, Veronika, “Construction of Türkmen coats”, Textile History 14,1 (1983): 3-27.

Göçek,

Fatma Müge, East Encounters West (

Göçek, Fatma Müge, Rise of the Bourgeoisie, Demise of Empire: Ottoman Westernization and Social Change (New York and Oxford, 1996).

Haldane,

Hall

Edward, Henry VIII, The Lives of the Kings (reprint of 1550 folio

edition), Vol 1 (

Howard,

Deborah,

Hunt, Alan, Governance of the Consuming Passions: A History of Sumptuary Law (New York, 1996).

İnalcık,

Halil and Donald Quataert, An Economic and Social History of the

Jirousek,

Charlotte, “From "Traditional" to "Mass Fashion

System": Dress Among Men in a Rural

Jirousek,

Charlotte, “More than Oriental Splendor: European and Ottoman Headgear,

1380-1580”, Dress, the Annual Journal of the Costume Society of

Jirousek, Charotte, “The Transition to Mass Fashion System Dress in the Later Ottoman Empire” in Donald Quataert ed., Consumption Studies and the History of the Ottoman Empire, 1550‑1922 (Albany, 2000): 201-241.

Kumbaracılar,

Lewis,

Bernard, The Muslim Discovery of

Lorck,

Melchior, Konstantinopel Unter Sultan Suleiman dem Grossen Aufgenomunen Im

Jahre 1559, British Library Manuscript: 146.1.10. 121 plates of Turkish

costumes, animals, and buildings inlaid on 45 sheets. (

MacKenzie,

John, Orientalism: History, Theory and the Arts (

Macleod, Dianne Sachko, “Cross Cultural Cross Dressing: Class, Gender and Modernist Sexual Identity” in Julie F. Codell and Dianne Sachko Macleod eds., Orientalism Transposed: the Impact of the Colonies on British Culture (Brookfield VT, 1998).

Mayer,

L. A., Mamluk Costume (

Micklewright,

Nancy, Tracing the Transformation in Women’s Dress in Nineteenth-century

Montagu, Mary Wortley, The Turkish Embassy Letters, edited by Malcolm Jack (London, 1994.)

Nicolay,

Nicholas, Nauigations, Peregrinations and Voyages, Made Into Turkie by

Nicholas Nicolay..containing Sundry Singularities Which the Author Hath There

Seene and Observed (

Olian, Jo Anne, “Sixteenth-Century

Costume Books”, Dress,

the Annual Journal of the Costume Society of

Özel, Mehmet, Folklorik

Türk Kıyafetleri (

Purchas,

Samuel, Purchas, His Pilgrimes (

Payne, Blanche; Geitel Winakor, and Jane Farrell-Beck. The History of Costume. (New York, 1992).

Pepys,

Samuel. Diary. (Robert Latham and William Matthews), vol. 7. (

Quataert,

Donald. "Clothing Laws, State and Society in the

Raby,

Julian.

Rodinson,

Maxime. Europe and the Mystique of Islam, translated by Roger

Vernius, (

Russell, Douglas A., Costume History and Style (Englewood Cliffs NJ, 1983).

Scarce, Jennifer, “Principles of Ottoman Turkish Costume” Costume 22 (1988): 144-167.

Scarce,

Jennifer, Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East (

Searight,

Sarah, The British in the

Sevin,

Nurettin, Onüç Asırlık Türk Kıyafetlerine

Bir Bakış, reprint of 1955 edition (

Stillman,

Yedida, Arab Dress From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times: A Short History

(

Tapan, Nazan,

“Sorguçlar [Crests]”, Sanat 3/6: 99-107.

Tavernier, John Baptiste, The Six

Voyages of Jean Baptiste Tavernier (London, 1678).

Vecellio, Cesare, Habiti Antichi et

Moderni di tutto il Mundo, reprint Venice, 1590 (New York, 1977).

von

Le Coq, Albert, Buried Treasures of Chinese Turkestan (

von Breydenbach, Bernhard, Peregrinationes

in Terram Sanctam, Erhard Reuwich, illustrator (Mainz, 1486).